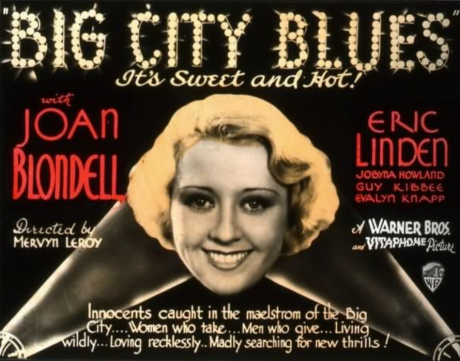

Warner Bros., 1932. Director: Mervyn LeRoy. Screenplay: Ward Morehouse and Lillie Hayward, based on Morehouse’s play New York Town. Camera: James Van Trees. Film editor: Ray Curtiss. Cast: Joan Blondell, Eric Linden, Jobyna Howland, Ned Sparks, Guy Kibbee, Grant Mitchell, Walter Catlett, Inez Courtney, Thomas Jackson.

The practice of starting the new year with a Warner Bros. pre-Code feature has been working out well in this column—and, as I’ve noted before, there’s a practically unlimited field of films to choose from. This month we have an entry that is, I think, far too often overlooked. An intimate story of ordinary people, produced on a deliberately “small” scale, Big City Blues is unquestionably a low-profile motion picture. But the viewer who seeks it out will be rewarded with a quietly uncompromising little drama that lingers in the memory long after the end of its brief running time.

One of the strongest qualities of the pre-Codes was their gritty, unsentimental view of the realities of life in those Depression-ridden years. Big City Blues is a good example: it takes a plot situation straight out of an optimistic rags-to-riches film of the 1920s and turns it on its head. Eric Linden, as a young innocent from a small rural town, comes to New York to seek his fortune—and immediately falls victim to the ways of the city, losing almost everything he owns within 48 hours. If this précis suggests an overripe stage melodrama, it’s important to add that the film was directed by Mervyn LeRoy, one of Warners’ “star” directors of the early 1930s. LeRoy was perfectly capable of depicting sensational story material on the screen (he had directed the gangster classic Little Caesar a scant two years earlier), but leavening it with intelligent, tasteful character touches. Linden may be a lamb among urban wolves, but both he and they are engaging, three-dimensional characters who hold our attention and keep the story moving.

Linden’s character, naive innocent though he is, believes he has prepared well for his transition to the big city: he has a well-connected cousin in New York who can guide and protect him. The cousin turns out to be Walter Catlett, one of the most colorful character players in Hollywood, cast here as a fast-talking opportunist who welcomes his young relative with open arms and dubious motives. It is soon revealed that Catlett is far less interested in Linden’s well-being than in his inheritance. Within minutes, Linden is swept into Catlett’s circle of friends, his savings diverted to the purchase of copious amounts of bootleg liquor. The day’s activities culminate in a party, the party turns dangerous, the cousin conveniently disappears, and soon Linden is on the run from the police. The one bright spot in his day is his introduction to a chorus girl, with whom he is instantly smitten. The chorine is played by Joan Blondell, who had come into her own at Warner Bros. by 1932. Easily the best-known star in this film, she gets top billing and delivers a sympathetic, nuanced performance.

Easily the best-known star in this film, she gets top billing and delivers a sympathetic, nuanced performance.

And Blondell, Linden, and Catlett are only the beginning of the cast list. I’ve made no secret of my affection (an affection shared by most film enthusiasts) for the legion of great character players who populated the films of Hollywood’s golden age. Big City Blues delivers a multitude of these beloved players, from glib, longwinded Catlett to sour-faced Ned Sparks to folksy Grant Mitchell and Edward McWade (at the small-town train station). Guy Kibbee is comfortably cast as a genial, incompetent house detective; Thomas Jackson appears in his patented characterization as the deadpan police inspector; the underappreciated Inez Courtney, a fixture in so many films of the 1930s, lends her quirky charm as Joan Blondell’s pal and fellow chorine. (Personally I’m pleased to see Josephine Dunn—a graduate of the Paramount Pictures School, about which I’ve written elsewhere—in a brief bit as an ill-fated party guest.) So rich is this cast list that Lyle Talbot and Humphrey Bogart, both of whom would become far more famous in later years, are not even given screen billing.

Not only is Big City Blues a worthy memento of the pre-Code period; given the relentless downhill course of Eric Linden’s fortunes, it may also qualify as an early example of film noir. Then again, perhaps not. The young protagonist is, not surprisingly, driven back to the safety of his small-town home within three days; but, uncharacteristically for film noir, he ends the story on a note of modest hope, nursing an ambition to return to the city and Joan Blondell at some later date. In any case, this movie, with its engaging storytelling and a well-loved cast of familiar faces, is recommended to the film enthusiast to get the new year off to a lively start.