In the course of researching the film adaptations of Snow White that preceded the Disney version—nearly all of them produced during the silent period—I found that Cinderella was, if anything, an even more popular silent-film subject than Snow White. Several of the Cinderella silents were, in fact, readily available for viewing and proved to be charming and intriguing in their own right. Searching them out became a new pursuit, entirely separate from my Snow White research. Obviously there was no place in the Snow White book to publish these findings, but this website seems like a good place for them. I’ll be updating this page as I find more information about these gems, and interested visitors who have additional information, and would like to share it, are welcome to do so here.

Cendrillon (Méliès/Star Film, 1899)

How appropriate that this key early film version of Cinderella was produced by Georges Méliès—not only because Méliès was, like Charles Perrault, a Frenchman; but also because, in the world of early cinema, he was the producer perhaps best suited to a fantasy of such delicate charm. Like so many early films based on literary sources, Cendrillon relies on the viewer’s familiarity with the story and serves to illustrate the plot, more than actually retelling it. By 1899 Méliès had begun to develop his cinematic bag of tricks, and this, his first version of Cinderella, is long on effects: the transformation of mice into footmen, of the pumpkin into a coach, and of Cinderella’s ragged clothes into a fine gown. Most of these transformations are accomplished in 1899 by stop-camera substitutions, but Méliès still relies heavily on his stock of theatrical techniques, and when Cinderella’s fairy godmother has finished working her magic, she exits the cottage by descending through a trap door in the stage.

How appropriate that this key early film version of Cinderella was produced by Georges Méliès—not only because Méliès was, like Charles Perrault, a Frenchman; but also because, in the world of early cinema, he was the producer perhaps best suited to a fantasy of such delicate charm. Like so many early films based on literary sources, Cendrillon relies on the viewer’s familiarity with the story and serves to illustrate the plot, more than actually retelling it. By 1899 Méliès had begun to develop his cinematic bag of tricks, and this, his first version of Cinderella, is long on effects: the transformation of mice into footmen, of the pumpkin into a coach, and of Cinderella’s ragged clothes into a fine gown. Most of these transformations are accomplished in 1899 by stop-camera substitutions, but Méliès still relies heavily on his stock of theatrical techniques, and when Cinderella’s fairy godmother has finished working her magic, she exits the cottage by descending through a trap door in the stage.

One camera effect may be overlooked by the modern viewer: Méliès incorporates several cross-dissolves in the course of the story. The picture follows Cinderella’s progress by dissolving from her cottage to the royal ball, and dissolves back again when she returns. After the Prince finds her, we dissolve again to the church exterior to see their wedding procession. In 1899, of course, these dissolves had to be performed in the camera, multiplying the complexities of Méliès’ stagecraft in producing this film. One always hesitates to use the word “first” carelessly, but cross-dissolves were undeniably an innovation at this point in history, and Charles Musser has ventured the claim that this was perhaps the first film to use them.

As for the story, we may note some distinctive touches even in this cursory telling of the tale. At the ball, Cinderella’s stepsisters break with tradition by recognizing her, even in her finery. They continue to snub her, and after she reverts to her ragged clothing at midnight, they lead the rest of the assemblage in cruelly ridiculing her. Cinderella returns to her cottage, still haunted by the tyranny of time, and plot again gives way to spectacle as Méliès inserts a ballet of giant timepieces. And at story’s end, as Cinderella and her Prince enter the church for their wedding, the camera remains outside to observe a charming group dance by assorted onlookers, ending with a “curtain call” tableau featuring the major characters.

Like many films of the period, Cendrillon was offered in 1899 in a hand-tinted color edition. A tantalizingly brief fragment of one of the color prints has survived, and is incorporated in the reconstruction on the Flicker Alley DVD.

Pathé productions, 1907-08

Pathé-Frères, the legendary French company that would produce La petite Blancheneige, a notable version of “Snow White,” in 1910, tackled “Cinderella” first with Cendrillon ou la pantoufle merveilleuse in 1907. Prints of Cendrillon were evidently produced with Pathé’s distinctive stencil-color process, as were prints of the later Blancheneige. The film was distributed in the U.S. as Cinderella, and a 1908 Cinderella, referenced in American trade journals but as yet unidentified, may well have been a reissue of the 1907 Pathé film. Coincidentally, that 1908 release was reviewed by Moving Picture World in the same issue—and on the same page—as another Pathé release known alternately as Donkey Skin and Donkey’s Skin. Although far less familiar to us today, “Donkeyskin” is actually a variant strain of the same folktale tradition that produced “Cinderella.” Maria Tatar discusses the links between the stories on pp. 102-06 of The Classic Fairy Tales , and also offers her translation of the Perrault version of “Donkeyskin,” which is reasonably close to the continuity of the 1908 Pathé film, judging by the extended synopsis in that same issue of Moving Picture World. I’ll be updating this entry as I learn more about these films.

Cinderella (Thanhouser, 1911)

Florence LaBadie, one of Thanhouser’s resident all-around leading ladies, makes a spunky and proactive Cinderella in this reel, filmed in the studio and, like most of Thanhouser’s product, among the environs of New Rochelle. This production was released late in 1911 as a special holiday attraction.

Florence LaBadie, one of Thanhouser’s resident all-around leading ladies, makes a spunky and proactive Cinderella in this reel, filmed in the studio and, like most of Thanhouser’s product, among the environs of New Rochelle. This production was released late in 1911 as a special holiday attraction.

The familiar story is told here in fairly straightforward fashion, with one interesting variation. Here Cinderella’s father—or, at any rate, a sympathetic male character—is present in the early scenes, and mounts a halfhearted defense of the heroine. But he’s a weak and ineffectual champion, and the stepmother and stepsisters make short work of him, contemptuously overruling both him and Cinderella.

As with most versions of the story, Cinderella’s magical makeover by the fairy godmother before the ball is a highlight of this film. Here the transformations of pumpkin, mice, and Cinderella’s gown are perfunctory, accomplished by stop-camera substitutions. But this version introduces an intriguing original idea: all these magical transformations take place inside the house. When the godmother’s work is finished, and Cinderella in all her splendor is inside the coach and ready to go to the ball, one whole wall of the house suddenly disappears! The horses pull the coach out into the street and continue on their way, and the wall reappears, restoring the original interior.

Cinderella (Selig, 1911)

By 1911 the Selig company was actively pursuing Western film production in authentic western locations, but its Chicago studio was also still as busy as ever and William Selig was still attempting to crack the feature-film market. This three-reel Cinderella, released in 1911 just after the Thanhouser one-reel version, was part of that effort. Selig recruited the well-known stage star Mabel Taliaferro, advertised her heavily in the title role, and lavished unusual promotional attention on the release, commissioning a special musical score and providing a special spoken lecture (a copy of which is preserved today in the Academy’s Selig collection) to accompany the film. Both the star and the film itself made a vivid impression on Vachel Lindsay, who wrote in 1915: “Mabel Taliaferro’s Cinderella, seen long ago, is the best film fairy-tale the present writer remembers.”

The film’s detailed synopsis indicates that this was a lavish and mostly faithful adaptation of the tale—with another variation. Here the Prince (T.J. Carrigan), to avoid being forced into an arranged marriage, fled his father’s castle in disguise, and he and Cinderella met in the first reel, each unaware of the other’s identity. This led to a plot complication later on, when Cinderella was “heartbroken” to discover that her romantic ideal was the Prince—apparently under the impression that he had forgotten her in the meantime. Needless to say, the two were reunited and all ended happily.

Cendrillon ou la pantoufle merveilleuse (Méliès/Pathé, 1912)

Comparison of this film

Comparison of this film with Méliès’ 1899 version offers a striking illustration of just how much his technique had advanced in the intervening years. With a running time nearly five times that of the earlier version, it’s hardly surprising that this Cendrillon is far more elaborate than its predecessor, in terms of both story and effects. This time the story is not merely illustrated but engagingly retold: we see the stepsisters abusing Cinderella at some length at the beginning of the story, and when the fairy godmother arrives, Cinderella regales her with a petulantly pantomimed account of the mistreatment she has had to endure. Late in the film, when Cinderella has disappeared, the Prince is visibly annoyed with his staff’s inability to find her. (When one emissary returns with a report of yet another fruitless search, the Prince impatiently shoves him backward, knocking down a row of other attendants like dominoes!) And the dynamics of the early scenes are sweetly reversed at film’s end, when the stepsisters, arriving at the wedding, are once again surprised to receive Cinderella’s forgiveness.

But this is a Méliès film, after all, and the plot takes a back seat to a spectacular display of screen- and stagecraft. The scene of the fairy godmother preparing Cinderella for the ball—transforming the pumpkin into a coach, continuing through the assembly of Cinderella’s retinue of footmen and servants, and climaxing with the appearance of her gown—is the centerpiece of the film, a sumptuous banquet of stage and movie magic that occupies about a third of the total footage. True to Méliès’ background, it’s staged like a conjurer’s performance: beginning with a nondescript staging area outside the house, cutting away as Cinderella gathers the mice, rats, and lizards that will be transformed by the godmother’s magic, then returning to the “stage” as more and more layers of extravagance are added, culminating in a lush theatrical tableau as Cinderella prepares to leave for the ball.

Like her counterpart in the 1899 Méliès film, Cinderella here is haunted by the specter of time. The hour of midnight is announced in abstractly visual terms in a charming vignette: a procession of twelve costumed figures parade across the screen, striking the hour on a chime. Eleven comely young ladies take their turns; the twelfth figure is Father Time himself, complete with hourglass and scythe. In place of the ballet of timepieces in the earlier film, Cinderella here is menaced by a single giant clock face. The twelve numerals are replaced by jeering faces and wagging fingers, then the entire circular frame gives way to the warning figure of the fairy godmother herself and her attendants.

Cinderella (Famous Players/Paramount, 1914)

Selig’s three-reel Cinderella had been ambitious enough in 1911, but Paramount upped the ante considerably with this 1914 feature. Although only one reel longer than the Selig effort, this one carried with it the prestige of the Famous Players name, and featured none other than Mary Pickford in the title role. For years it was considered a lost film, but then it resurfaced in Amsterdam and happily has been restored to view

Selig’s three-reel Cinderella had been ambitious enough in 1911, but Paramount upped the ante considerably with this 1914 feature. Although only one reel longer than the Selig effort, this one carried with it the prestige of the Famous Players name, and featured none other than Mary Pickford in the title role. For years it was considered a lost film, but then it resurfaced in Amsterdam and happily has been restored to view.

As played by Mary Pickford, Cinderella is, essentially, Mary Pickford (albeit a bit more subdued than usual). This is an important distinction; of the surviving films discussed here, this is the earliest one to personalize Cinderella to such a degree, giving us a heroine who engages our sympathy, along with the magic and enchantment of the traditional tale. Kevin Brownlow has pointed out that the effects in this film are no match for Méliès, but the film compensates with winning moments of humanity. Cinderella, ordered by her fairy godmother to bring in the mice and rats, obediently carries the cages but holds them gingerly at arm’s length, her fear and revulsion clearly evident. Later, delayed in escaping from the ball, she’s descending the palace steps when her coach, horses, and fine gown disappear before her eyes, replaced by the mice, pumpkin, and familiar old rags. Cut to a closeup of Mary, surveying the change sadly—not wallowing in self-pity, but registering a quiet pathos that underlines the poignance of lost illusions. Owen Moore is less than satisfactory as Prince Charming, but he was still married to Mary and was probably cast accordingly.

And at that (as Kevin has also pointed out), the camera effects in this film are far more than adequate. Much is made of cross-dissolves, not only to transform the pumpkin and mice into coach and horses, and vice versa, but also to reveal an army of fairies in the forest and to portray the dream visions of sleeping or daydreaming characters.

And at that (as Kevin has also pointed out), the camera effects in this film are far more than adequate. Much is made of cross-dissolves, not only to transform the pumpkin and mice into coach and horses, and vice versa, but also to reveal an army of fairies in the forest and to portray the dream visions of sleeping or daydreaming characters.

Some interesting creative liberties are taken with the story in the early scenes of this film. The fairy godmother (Inez Marcel) is introduced in the guise of a beggar woman. Approaching the stepmother and stepsisters in the street, she is rudely rebuffed, but Cinderella treats her with kindness and fetches her bread and water. The beggar is then magically revealed as the fairy godmother, and Cinderella, having “entertained angels unawares,” enjoys the benefit of her providence. Sent by her stepmother to the forest to gather firewood, Cinderella is magically supplied with the aforementioned host of fairies to help with her work. At this point, as in the Selig Cinderella, she has an early meeting with the Prince, but here he’s in the woods hunting with his friends. When his loutish companions laugh and deride the peasant girl, the Prince gallantly defends her.

Once the stepmother and stepsisters leave for the ball, the story proceeds along familiar lines—although, even then, there are some charming or humorous departures, some of them apparently improvised. (When Cinderella arrives at the ball she doesn’t immediately go inside; distracted by her apparently immobile footman, she can’t resist poking at him and tickling him to provoke a reaction. Meanwhile, inside the palace, as the procession of prospective brides parades past the Prince, he becomes so alarmed at the spectacle of Cinderella’s homely stepsisters that he hides behind his throne until the coast is clear!) After returning home, Mary, like the Méliès Cinderellas, is haunted by the tyranny of time; here we see her asleep as a dream vision of a clock is superimposed above her. Two little figures emerge to strike their hammers against the clock’s chimes and soon proceed to striking each other instead, while the hands and numerals of the clock face, via stop-motion animation, go crazily awry.

Aschenputtel (Lotte Reiniger, 1922)

Lotte Reiniger, the master of silhouette animation best remembered today for The Adventures of Prince Achmed, produced numerous short films as well, including this version of the “Cinderella” story. Viewers familiar with Reiniger’s other films will recognize her signature touches of charm and invention, for example her staging, making creative use of masked areas of the film frame. In an early scene Cinderella sits dejectedly, isolated in the lower left corner of the screen, the rest of the frame a solid black. A second, seemingly unrelated vignette opens in the upper right corner, depicting the stepsisters in an upper room. Then a third area is revealed in between, showing the stepmother on a staircase that connects the upper and lower floors, and suddenly we see that the three isolated areas are actually one continuous cross-section of the house.

Along with its imaginative technique, this film is notable for its storytelling. The plot of “Cinderella” familiar to most of us today stems from the French version published by Charles Perrault in the late 17th century, and most of the silent films discussed above are clearly based on that model. But in the meantime the Brothers Grimm had published a very different “Aschenputtel” (“Cinderella”) in 1812, and Reiniger’s film, produced in Germany, preserves some elements from their version. Here we see Cinderella forced to pick lentils out of the fireplace ashes; the birds that help her with these and other tasks; the heroine praying at her mother’s grave; the tree that magically provides Cinderella with her ball gown; and the stepsister who hacks off a large chunk of her own foot to fit it into the slipper—which is then drenched with blood!

Cinderella/Der Verlorene Schuh (Decla-Bioskop, 1923)

For those of us who love Nosferatu, Metropolis, and the other dark works of 1920s German cinema, “The Other Weimar” (as it was styled in a special 2007 retrospective at the Giornate) can be a real revelation. Ludwig Berger’s landmark 1923 feature Cinderella is an excellent case in point. No ominous shadows or expressionistic horror here: this was a charming, lively, and quite lavishly produced version of the tale, taking numerous creative liberties but always delightful ones, and faithful to the spirit of the story. Sadly, the film survives today in a two-reel version created for the home-movie market, but even in this drastically reduced fragment, what’s left is reasonably coherent and a pure delight. (Cinderella was shown theatrically in the U.S. in 1927, and the New York Times review indicates that key episodes were missing even as early as that date.)

Like the Reiniger film discussed above, this other German film preserves some elements from the Brothers Grimm, along with some of the Perrault standbys and some delightful inventions apparently hatched by Berger himself. The fairy godmother (Frieda Richard) plays a strong and proactive role here, not only providing the magic that enables Cinderella to attend the ball, but stepping in on numerous other occasions to help her out of some difficulty. The scene of Cinderella’s escape from the ball, just before the stroke of midnight, demonstrates the film’s charm and cinematic invention: as she nears the palace doorway, her coach, visible just outside, suddenly explodes and is replaced by a clock tower reminding her of the time. She evades the pursuing Prince and crosses a lovely little bridge with an ornate covered section in the center and breakaway sections at either end. When the Prince reaches the bridge, the godmother causes the outer sections to swing away from the center, stranding him there, then tosses a cloak of invisibility over Cinderella, who uses it to disappear and make her escape.

The loss of the complete feature version of this film is one of the egregious losses of the silent era. Paul Rotha wrote of it: “The touch of Ludwig Berger seemed magical, so completely entrancing was the subtle fabrication of this exquisite work.”

Three updated variations:

Cinderella Up-to-Date (Méliès/Star Film, 1909)

Cinderella Up-to-Date (Méliès/Star Film, 1909)

A Modern Cinderella (Vitagraph, 1910)

A Modern Cinderella (Edison, 1911)

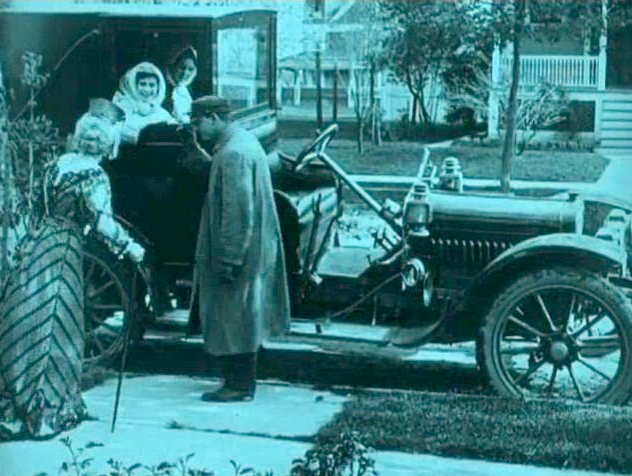

Like some of today’s filmmakers, some silent-era filmmakers couldn’t resist the idea of updating the Cinderella theme to their own time. Georges Méliès, in addition to his faithful adaptations, produced in 1909 a contemporary comedy about a girl who buys a pair of shoes and loses one of them. The man who finds the shoe places a classified ad, and he and the girl meet and eventually marry—the attendant publicity prompting a new craze: shoes bought and deliberately lost by women seeking romance! Vitagraph’s A Modern Cinderella actually did transpose the Cinderella tale to a contemporary setting, with the heroine (Mary Fuller) and her stepsister rooming together in a boarding house. Here the fairy godmother was a fellow boarder, an older lady, apparently of some means, who took an interest in Cinderella, bought her a new wardrobe, and provided her own limousine to take the girl to the ball. There Cinderella met the kind lady’s grandson, who later discovered her misplaced shoe, traced it to her through the shoe store, and was reunited with her for a happy ending. This picture survives today, and—although the stepsister’s suppression of Cinderella is a little harder to accept in the egalitarian context of twentieth-century American society—is quite a charming little film. It can be seen online, thanks to the National Film Preservation Foundation. The following year, after leaving Vitagraph and joining the Edison forces, Mary Fuller starred in a second film also titled A Modern Cinderella. But here, as with the Méliès comedy, the connection with “Cinderella” was a loose one: Mary removed her shoes and stockings to go wading at the beach and was surprised there by an admirer (Darwin Kerr), who appropriated one of the shoes and later used it as a bargaining chip to become better acquainted with her.

And, of course …

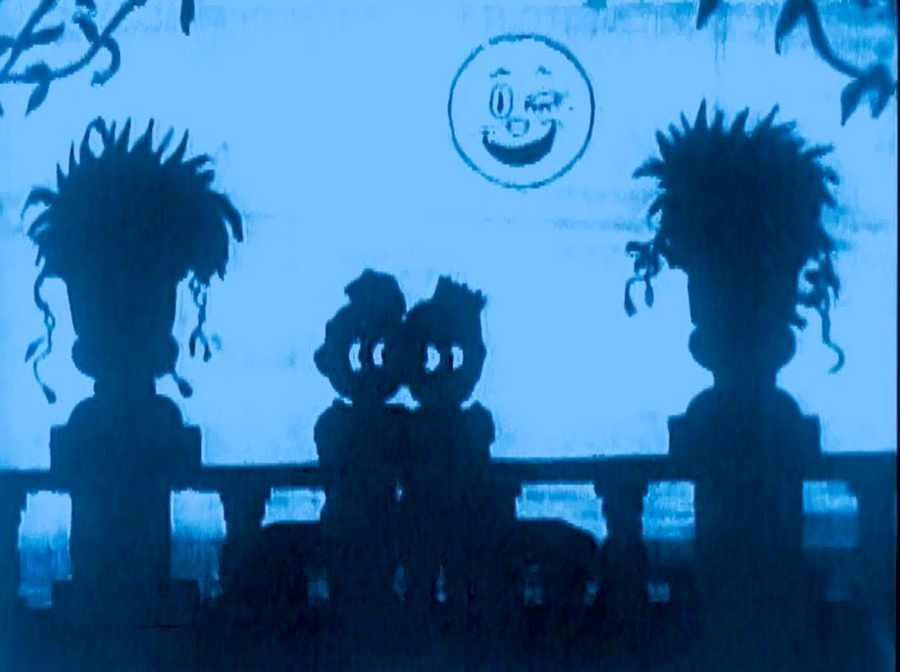

Cinderella (Laugh-O-gram, 1922)

Lest we forget, Walt Disney himself produced a version of “Cinderella” during the silent period—although his version was, by definition, about as loose as an adaptation can get. This Cinderella was one of the Laugh-O-grams, the series of “modernized fairy tales” that Walt and his friends produced in Kansas City at the very beginning of their animation careers. Here the traditional tales were deliberately satirized and used as springboards for a series of contemporary Jazz Age gags, and Cinderella was no exception. In fact, considering the playful satire of the young Laugh-O-gram artists, it’s surprising how much of the traditional romantic mood of the tale survives in this reel. As subsequent decades of cartoon production would reveal, something about the “Cinderella” story beguiled the most mischievous cartoon-makers who set out to lampoon it. Even that inveterate prankster Tex Avery indulged in a fleeting romantic interlude in his 1938 Warner Bros. short Cinderella Meets Fella. In this Laugh-O-gram version, Walt and company interrupt their irreverent gags and non-sequitur puns long enough to allow Cinderella and her Prince a brief moonlit moment on the balcony, their silhouetted figures outlined against the night sky. It’s a nice moment, achieved with the most basic of production resources—modestly suggesting the charming fantasy worlds that Walt would later create on the screen in the sound era.